American Civil War: The final day of the Battle of Gettysburg culminates with Pickett’s Charge.

Tag Archives: 1863

31 October 1863

The New Zealand Wars resume as British forces in New Zealand led by General Duncan Cameron begin their Invasion of the Waikato.

[rdp-wiki-embed url=’https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_Zealand_Wars’]

26 October 1863

The Football Association is founded.

[rdp-wiki-embed url=’https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Football_Association’]

1 July 1863

The Battle of Gettysburg begins.

[rdp-wiki-embed url=’https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Gettysburg’]

18 May 1863

The Siege of Vicksburg begins.

From the spring of 1862 until July 1863, during the American Civil War, Union forces waged a campaign to take the Confederate stronghold of Vicksburg, Mississippi, which lay on the east bank of the Mississippi River, halfway between Memphis to the north and New Orleans to the south. The Siege of Vicksburg divided the Confederacy and proved the military genius of Union General Ulysses S. Grant.

Vicksburg was one of the Union’s most successful campaigns of the war. Although General Ulysses S. Grant’s first attempt to take the city failed in the winter of 1862-63, he renewed his efforts in the spring. Admiral David Porter had run his flotilla past the Vicksburg defenses in early May as Grant marched his army down the west bank of the river opposite Vicksburg, crossed back to Mississippi and drove toward Jackson. After defeating a Confederate force near Jackson, Grant turned back to Vicksburg. On May 16, he defeated a force under General John C. Pemberton at Champion Hill. Pemberton retreated back to Vicksburg, and Grant sealed the city by the end of May. In three weeks, Grant’s men marched 180 miles, won five battles and captured some 6,000 prisoners.

Grant made some attacks after bottling Vicksburg but found the Confederates well entrenched. Preparing for a long siege, his army constructed 15 miles of trenches and enclosed Pemberton’s force of 29,000 men inside the perimeter. It was only a matter of time before Grant, with 70,000 troops, captured Vicksburg. Attempts to rescue Pemberton and his force failed from both the east and west, and conditions for both military personnel and civilians deteriorated rapidly. Many residents moved to tunnels dug from the hillsides to escape the constant bombardments. Pemberton surrendered on July 4, and President Abraham Lincoln wrote that the Mississippi River “again goes unvexed to the sea.”

30 March 1863

The Danish prince Wilhelm Georg is chosen as King George of Greece.

George l; born Prince William of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg; was King of Greece from 1863 until his assassination in 1913.

George l; born Prince William of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg; was King of Greece from 1863 until his assassination in 1913.

Originally a Danish prince, George was born in Copenhagen, and seemed destined for a career in the Royal Danish Navy. He was only 17 years old when he was elected king by the Greek National Assembly, which had deposed the unpopular former king Otto. His nomination was both suggested and supported by the Great Powers: the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, the Second French Empire and the Russian Empire. He married the Russian grand duchess Olga Constantinovna of Russia, and became the first monarch of a new Greek dynasty. Two of his sisters, Alexandra and Dagmar, married into the British and Russian royal families. King Edward VII and Tsar Alexander III were his brothers-in-law and King George V and Tsar Nicholas II were his nephews.

George’s reign of almost 50 years was characterized by territorial gains as Greece established its place in pre-World War I Europe. Britain ceded the Ionian Islands peacefully, while Thessaly was annexed from the Ottoman Empire after the Russo-Turkish War. Greece was not always successful in its territorial ambitions; it was defeated in the Greco-Turkish War. During the First Balkan War, after Greek troops had captured much of Greek Macedonia, George was assassinated in Thessaloniki. Compared with his own long tenure, the reigns of his successors Constantine, Alexander, and George II proved short and insecure.

George was born at the Yellow Palace, an 18th-century town house at 18 Amaliegade, right next to the Amalienborg Palace complex in Copenhagen. He was the second son and third child of Prince Christian of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg and Princess Louise of Hesse-Kassel. Until his accession in Greece, he was known as Prince William, the namesake of his grandfathers William, Duke of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg, and Prince William of Hesse-Kassel.

George and his family, 1862: Frederick, Christian IX, George; Dagmar, Valdemar, Queen Louise, Thyra, Alexandra

Although he was of royal blood, his family was relatively obscure and lived a comparatively normal life by royal standards. In 1853, however, George’s father was designated the heir presumptive to the childless King Frederick VII of Denmark, and the family became princes and princesses of Denmark. George’s siblings were Frederick who succeeded their father as King of Denmark, Alexandra who became wife of King Edward VII of the United Kingdom and the mother of King George V, Dagmar, Thyra and Valdemar.

George’s mother tongue was Danish, with English as a second language. He was also taught French and German. He embarked on a career in the Royal Danish Navy, and enrolled as a naval cadet along with his elder brother Frederick. While Frederick was described as “quiet and extremely well-behaved”, George was “lively and full of pranks”.

Following the overthrow of the Bavarian-born King Otto of Greece in October 1862, the Greek people had rejected Otto’s brother and designated successor Luitpold, although they still favored a monarchy rather than a republic. Many Greeks, seeking closer ties to the pre-eminent world power, Great Britain, rallied around Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, second son of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. British prime minister Lord Palmerston believed that the Greeks were “panting for increase in territory”, hoping for a gift of the Ionian Islands, which were then a British protectorate. The London Conference of 1832, however, prohibited any of the Great Powers’ ruling families from accepting the crown, and in any event, Queen Victoria was adamantly opposed to the idea. The Greeks nevertheless insisted on holding a plebiscite in which Prince Alfred received over 95% of the 240,000 votes. There were 93 votes for a Republic and 6 for a Greek. King Otto received one vote.

With Prince Alfred’s exclusion, the search began for an alternative candidate. The French favored Henri d’Orléans, duc d’Aumale, while the British proposed Queen Victoria’s brother-in-law Ernest II, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, her nephew Prince Leiningen, and Archduke Maximilian of Austria, among others. Eventually, the Greeks and Great Powers winnowed their choice to Prince William of Denmark, who had received 6 votes in the plebiscite. Aged only 17, he was elected King of the Hellenes on 30 March 1863 by the Greek National Assembly under the regnal name of George I. Paradoxically, he ascended a royal throne before his father, who became King of Denmark on 15 November the same year. There were two significant differences between George’s elevation and that of his predecessor, Otto. First, he was acclaimed unanimously by the Greek Assembly, rather than imposed on the people by foreign powers. Second, he was proclaimed “King of the Hellenes” instead of “King of Greece”, which had been Otto’s style.

His ceremonial enthronement in Copenhagen on 6 June was attended by a delegation of Greeks led by First Admiral and Prime Minister Constantine Kanaris. Frederick VII awarded George the Order of the Elephant, and it was announced that the British government would cede the Ionian Islands to Greece in honor of the new monarch.

The new 17-year-old king toured Saint Petersburg, London and Paris before departing for Greece from the French port of Toulon on 22 October aboard the Greek flagship Hellas. He arrived in Athens on 30 October 1863, after docking at Piraeus the previous day. He was determined not to make the mistakes of his predecessor, so he quickly learned Greek. The new king was seen frequently and informally in the streets of Athens, where his predecessor had only appeared in pomp. King George found the palace in a state of disarray, after the hasty departure of King Otto, and took to putting it right by mending and updating the 40-year-old building. He also sought to ensure that he was not seen as too influenced by his Danish advisers, ultimately sending his uncle, Prince Julius, back to Denmark with the words, “I will not allow any interference with the conduct of my government”. Another adviser, Count Wilhelm Sponneck, became unpopular for advocating a policy of disarmament and tactlessly questioning the descent of modern Greeks from classical antecedents. Like Julius, he was dispatched back to Denmark.

From May 1864, George undertook a tour of the Peloponnese, through Corinth, Argos, Tripolitsa, Sparta, and Kalamata, where he embarked on the frigate Hellas. Proceeding northwards along the coast accompanied by British, French and Russian naval vessels, the Hellas reached Corfu on 6 June, for the ceremonial handover of the Ionian Islands by the British High Commissioner, Sir Henry Storks.

Politically, the new king took steps to conclude the protracted constitutional deliberations of the Assembly. On 19 October 1864, he sent the Assembly a demand, countersigned by Constantine Kanaris, explaining that he had accepted the crown on the understanding that a new constitution would be finalized, and that if it was not he would feel himself at “perfect liberty to adopt such measures as the disappointment of my hopes may suggest”. It was unclear from the wording whether he meant to return to Denmark or impose a constitution, but as either event was undesirable the Assembly soon came to an agreement.

On 28 November 1864, he took the oath to defend the new constitution, which created a unicameral assembly with representatives elected by direct, secret, universal male suffrage, a first in modern Europe. A constitutional monarchy was set up with George deferring to the legitimate authority of the elected officials, although he was aware of the corruption present in elections and the difficulty of ruling a mostly illiterate population. Between 1864 and 1910, there were 21 general elections and 70 different governments.

Internationally, George maintained a strong relationship with his brother-in-law, the Prince of Wales, and sought his help in defusing the recurring and contentious issue of Crete, an overwhelmingly Greek island that remained under Ottoman Turk control. Since the reign of Otto, the Greek desire to unite Greek lands in one nation had been a sore spot with the United Kingdom and France, which had embarrassed Otto by occupying the main Greek port Piraeus to dissuade Greek irredentism during the Crimean War. During the Cretan Revolt, the Prince of Wales sought the support of British Foreign Secretary Lord Derby to intervene in Crete on behalf of Greece. Ultimately, the Great Powers did not intervene and the Ottomans put down the rebellion.

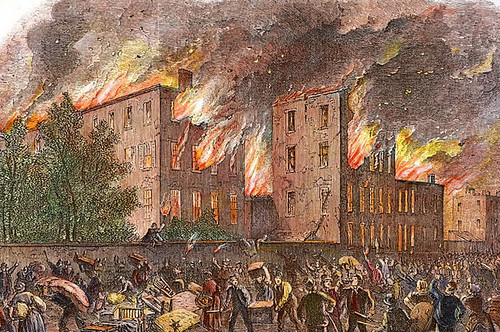

13 July 1863

Opponents of conscription begin three days of rioting in New York City.

On July 13, 1863, as the second day of a new military draft lottery in New York City got underway, demonstrations broke out across the city in what began as an organized opposition to the first federally mandated conscription laws in the nation’s history, but soon morphed into a violent uprising against the city’s wealthy elite; its African-American residents; and the very idea of the Civil War itself. The New York City Draft Riots, which would wreak havoc on the city for four days and remain the largest civilian insurrection in American history, exposed the deep racial, economic and social divides that threatened to tear the nation’s largest city apart in the midst of the American Civil War.

Thanks to its status as the business capital of the United States, New York City was a deeply divided city at the start of the Civil War in April 1861. Its merchants and financial institutions were loath to lose their southern business and the city’s then-mayor, Fernando Wood, had called for the city to secede from the Union. Meanwhile, to the city’s poorer citizens, the war increasingly came to be seen as benefitting only the rich, as the coffers of the city’s elites filled with the financial spoils of battle and the conflict became known as a “rich man’s war, poor man’s battle.” The passage of the nation’s first military draft act, in March 1863, only worsened the situation. Not only did it allow men to buy their way out of military service by paying a commutation fee of $300 , it also exempted blacks from the draft, as they were not yet considered American citizens. Opposition to the draft was widespread across the North, and in New York, some of the loudest critics of the bill could be found in city government, as politicians railed against the legality of the bill and its impact on the city’s working class poor.

1 July 1863

The Battle of Gettysburg begins.

The largest military conflict in North American history begins this day when Union and Confederate forces collide at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. The epic battle lasted three days and resulted in a retreat to Virginia by Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia.

Two months prior to Gettysburg, Lee had dealt a stunning defeat to the Army of the Potomac at Chancellorsville, Virginia. He then made plans for a Northern invasion in order to relieve pressure on war-weary Virginia and to seize the initiative from the Yankees. His army, numbering about 80,000, began moving on June 3. The Army of the Potomac, commanded by Joseph Hooker and numbering just under 100,000, began moving shortly thereafter, staying between Lee and Washington, D.C. But on June 28, frustrated by the Lincoln administration’s restrictions on his autonomy as commander, Hooker resigned and was replaced by George G. Meade.

Meade took command of the Army of the Potomac as Lee’s army moved into Pennsylvania. On the morning of July 1, advance units of the forces came into contact with one another just outside of Gettysburg. The sound of battle attracted other units, and by noon the conflict was raging. During the first hours of battle, Union General John Reynolds was killed, and the Yankees found that they were outnumbered. The battle lines ran around the northwestern rim of Gettysburg. The Confederates applied pressure all along the Union front, and they slowly drove the Yankees through the town.

By evening, the Federal troops rallied on high ground on the southeastern edge of Gettysburg. As more troops arrived, Meade’s army formed a three-mile long, fishhook-shaped line running from Culp’s Hill on the right flank, along Cemetery Hill and Cemetery Ridge, to the base of Little Round Top. The Confederates held Gettysburg, and stretched along a six-mile arc around the Union position. Lee’s forces would continue to batter each end of the Union position, before launching the infamous Pickett’s Charge against the Union center on July 3.

1 July 1863

The Battle of Gettysburg starts.

10 January 1863

The world’s oldest underground railway (London) opens between London Paddington station and Farringdon station.