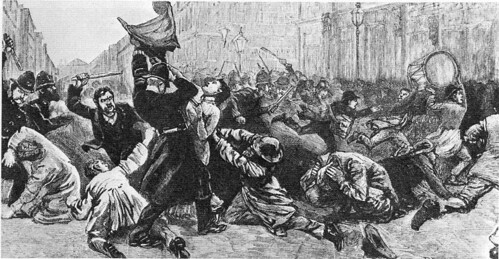

The ‘Bloody Sunday’ clashes take part in central London.

There are several events which are remembered with the name ‘Bloody Sunday,’ perhaps most famously Sunday the 30th of January 1972 when members of the British Army opened fire on protesters in Derry, Ireland, killing 13. London has its own Bloody Sunday however, which took place on Sunday the 13th of November 1887, in Trafalgar Square. It was the culmination of months of increasing tension between police and Londoners over the right to demonstrate in Trafalgar Square.

Demonstrations by the unemployed had been taking place in the square daily since the summer. Many unemployed men and women also slept in the square, washing in the fountains. Under pressure from the press to deal with a situation seen as embarrassing to the great metropolis, the police started to disperse meetings in the square from the 17th of October, often resorting to violence. The tension continued, now with frequent clashes between police and protesters, and Irish Home Rulers also began to use the square to protest.

Sir Charles Warren, Commissioner of Police, banned all meetings in Trafalgar Square on the 8th of November. This challenge to the freedom of speech and the right to protest ouraged radicals across London, and a meeting scheduled for the following Sunday suddenly became much more significant. Called initially to demand the release of the Irish MP William O’Brien from prison, the demonstration was a clear and deliberate defiance of the ban, and the police could not allow it to go ahead without suffering severe humiliation.