British authorities announce they have uncovered the Soviet Portland Spy Ring in London.

Tag Archives: 1961

12 February 1961

The Soviet Union launches Venera 1 towards Venus.

[rdp-wiki-embed url=’https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Venera_1′]

12 February 1961

The USSR launches Venera 1 towards Venus.

On November 16, 1965, Soviet spacecraft Venera 3 was launched. The Venera program space probe was built and launched by the Soviet Union to explore the surface of Venus. It possibly crashed on Venus on 1 March 1966, possibly making Venera 3 the first space probe to hit the surface of another planet.

The Venera Series Space Probes

The Venera series space probes were developed by the Soviet Union between 1961 and 1984 to gather data from Venus, Venera being the Russian name for Venus. The first Soviet attempt at a flyby probe to Venus was launched on February 4, 1961, but failed to leave Earth orbit. In keeping with the Soviet policy at that time of not announcing details of failed missions, the launch was announced under the name Tyazhely Sputnik “Heavy Satellite”. It is also known as Venera 1VA. Venera 1 and Venera 2 were intended as fly-by probes to fly past Venus without entering orbit. Venera 1 , also known as Venera-1VA No.2 and occasionally in the West as Sputnik 8 was launched on February 12, 1961. Telemetry on the probe failed seven days after launch. It flew past Venus on 19 May. However, since radio contact with the probe was lost before the flyby, no data could be returned. It is believed to have passed within 100,000 km of Venus and remains in heliocentric orbit. With the help of the British radio telescope at Jodrell Bank, some weak signals from Venera 1 may have been detected in June. Soviet engineers believed that Venera-1 failed due to the overheating of a solar-direction sensor.

Venera 2 also Lost

Venera 2 launched on November 12, 1965, but also suffered a telemetry failure after leaving Earth orbit. The Venera 2 spacecraft was equipped with cameras, as well as a magnetometer, solar and cosmic x-ray detectors, piezoelectric detectors, ion traps, a Geiger counter and receivers to measure cosmic radio emissions The spacecraft made its closest approach to Venus at 02:52 UTC on 27 February 1966, at a distance of 23,810 km. During the flyby, all of Venera 2’s instruments were activated, requiring that radio contact with the spacecraft be suspended. The probe was to have stored data using onboard recorders, and then transmitted it to Earth once contact was restored. Following the flyby the spacecraft failed to reestablish communications with the ground. It was declared lost on 4 March. An investigation into the failure determined that the spacecraft had overheated due to a radiator malfunction. Several other failed attempts at Venus flyby probes were launched by the Soviet Union in the early 1960s, but were not announced as planetary missions at the time, and hence did not officially receive the “Venera” designation.

25 January 1961

101 Dalmatians is premiered from Walt Disney Productions.

One Hundred and One Dalmatians, often abbreviated as 101 Dalmatians, is a 1961 American animated adventure film produced by Walt Disney and based on the 1956 novel The Hundred and One Dalmatians by Dodie Smith.

The 17th Disney animated feature film, the film tells the story of a litter of Dalmatian puppies who are kidnapped by the villainous Cruella de Vil, who wants to use their fur to make into coats. Their parents, Pongo and Perdita, set out to save their children from Cruella, all the while rescuing 84 additional puppies that were bought in pet shops, bringing the total of Dalmatians to 101.

Originally released to theaters on January 25, 1961, by Buena Vista Distribution, One Hundred and One Dalmatians was a box office success, pulling the studio out of the financial slump caused by Sleeping Beauty, a costlier production released two years prior.

Aside from its box office revenue, its commercial success was due to the employment of inexpensive animation techniques—such as using xerography during the process of inking and painting traditional animation cels—that kept production costs down. It was remade into a live-action film in 1996.

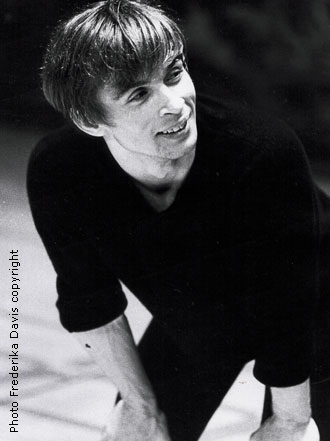

16 June 1961

The dancer, Rudolf Nureyev defects from the Soviet Union.

It was one of the most high profile defections of the Cold War, as one of the Soviet Union’s most celebrated figures turned his back on his native country, penetrated the Iron Curtain and defied the all-powerful KGB to claim a new life in the West. In many ways he was the first true male ballet dancer, an art form previously dominated by women with men merely as support, Nureyev pioneering a new appreciation of masculine performance as well as the beginnings of a fusion between ballet and modern dance, another area in which he excelled. Despite the revelation in later years that Nikita Krushchev signed an order to have him assassinated, it would be AIDS which would finally claim his life when he became one of the illness’s most high-profile early victims in the early 90’s. In many ways, his sexuality is key to an understanding of his interesting life, coloured as it was by non-conformity, impatience and his audacious bid to break free from an oppressive and controlling regime.

His beginnings couldn’t really have been any more Russian: he was born on a Trans-Siberian train near Irkutsk in the spring of 1938, his mother travelling to Vladivostock where his father was stationed as a Red Army political commissar. His early life was spent in Ufa in the little-known Republic of Bashkortostan between the Volga and the Urals and his introduction to ballet came at an early age when his mother took him and his sisters to a performance of “Song of the Cranes”. Folk dancing was common in Russia at the time and his talent was noticed very early on, his teachers encouraging him to train in Leningrad but this was a strange time for a Soviet Union segueing from World War to Cold War, causing major upheaval in cultural life, thus preventing Rudolf from fulfilling his dreams. In 1955 though, at the age of 17, he was accepted by the Leningrad Choreographic School which was attached to the infamous Kirov Ballet. He caught the eye of the renowned ballet master Alexander Pushkin who also later trained Mikhail Baryshnikov, another well-known defector, escaping to Canada in 1974, and of course also infamous as Sex and the City’s Petrovsky who moved him in with his family and helped him make the leap to Kirov. He would remain there for 3 years after graduation, dancing 15 roles and soaring to heights of popular consciousness across a divided Europe. However, after early European tours he was told by the Ministry of Culture that he would not be allowed to travel again.

His rebellious and non-conformist attitude made him a high defection risk and the level of esteem with which he was held in the Soviet Union meant that the authorities were desperate to make sure he didn’t become a national embarrassment. Thus, he was barred from a major European tour by the Kirov Ballet, designed as a hugely significant global display of Communist cultural superiority over the West. In a twist of fate though, the company’s leading male dancer Konstantin Sergeyev was injured and Nureyev was the only obvious replacement, buying him a ticket to Paris. There, he was received with rapturous applause by the French audience and he began to mingle with these foreigners, ruffling feathers among the nervous Kirov management who had expressly forbidden such a thing. The KGB ordered him back to Russia to perform a special dance at the Kremlin rather than accompany his colleagues to London, which Nureyev guessed was a lie and so he refused, whereupon he was told that his mother was severely ill. He didn’t believe them and became convinced that if he did return he would be imprisoned, so when he arrived at Le Bourget Airport on this day in 1961, he defected with the help of French police. He was immediately signed up by the Grand Ballet du Marquis de Cuevas and resumed his career by performing in “The Sleeping Beauty”.

On a tour of Denmark, he would meet the love of his life, Danish ballet sensation Erik Bruhn, over a decade older than Nureyev, though the two would remain together for 25 years until Bruhn’s death from lung cancer in 1986. Bruhn helped Nureyev handle the guilt of abandoning his family, particularly his beloved mother, in Russia and it was not until 1987, with the Cold War finally thawing, that Mikhail Gorbachev allowed him back home to visit her on her deathbed. He finally danced with the Kirov Ballet again in Leningrad in 1989, where he was reunited with many of the teachers and colleagues he hadn’t seen in over a quarter of a century. In the meantime, he had become a European star, offered a contract to join the UK’s Royal Ballet in 1962 as their Principal Dancer, a collaboration which would last 8 years and famously partner him with Dame Margot Fonteyn. He remained affiliated with the Royal Ballet thereafter as a Principal Guest Artist until the 1980’s when he committed to the Paris Opera Ballet as a director. He and Fonteyn would continue to perform together for many years though, their last performance together when she was 69 years of age and Nureyev 50 in 1988, he once commenting that they danced with “one body, one soul”. The 1970’s also found him in the United States, most famously in a revival of “The King & I”. Renowned as volatile and impatient, he was also praised for his generosity of spirit and his loyalty towards his friends, many ballerinas of the era crediting him with helping them through tough times in their careers.

In 1984, Nureyev tested positive for HIV at a time when that disease was just beginning to grab major world headlines as a new and vicious killer. Nureyev simply carried on regardless and it would be another 7 years before his health would seriously begin to decline, then in the spring of 1992 he entered the final phase of the disease. He made one final visit to a newly-democratic Russia before returning to New York one last time to conduct “Romeo & Juliet” at the American Ballet Theater Benefit in the Metropolitan Opera House. He brought the house down and later that year made his final public appearance at the Paris Opera overseeing the first Western performance of La Bayadere since the Russian Revolution, fulfilling a lifelong dream. That night, the French Culture Minister Jack Lang presented him with “the Commandeur de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres”, a real honour, though it was obvious to everyone that he was nearing the end of his life. 6 weeks later he entered a Parisian hospital and died there the following January, aged 54. His funeral was then held at the Paris Opera and he was buried in a Russian cemetery just outside the city which had first provided him with refuge 3 decades earlier. His coffin was lowered into the ground to music from the last act of “Giselle”.

17 April 1961

A group of Cuban exiles financed and trained by the CIA lands at the Bay of Pigs in Cuba with the aim of ousting Fidel Castro.

The Bay of Pigs Invasion was a failed military invasion of Cuba undertaken by the Central Intelligence Agency CIA-sponsored paramilitary group Brigade 2506 on 17 April 1961. A counter-revolutionary military group, trained and funded by the CIA, Brigade 2506 fronted the armed wing of the Democratic Revolutionary Front and intended to overthrow the increasingly communist government of Fidel Castro. Launched from Guatemala and Nicaragua, the invading force was defeated within three days by the Cuban Revolutionary Armed Forces, under the direct command of Castro.

The coup of 1952 led by General Fulgencio Batista, an ally of the United States, against President Carlos Prio, forced Prio into exile to Miami, Florida. Prio’s exile was the reason for the 26th July Movement led by Castro. The movement, which did not succeed until after the Cuban Revolution of 31 December 1958, severed the country’s formerly strong links with the US after nationalizing American economic assets.

It was after the Cuban Revolution of 1959, that Castro forged strong economic links with the Soviet Union, with which, at the time, the United States was engaged in the Cold War. US President Dwight D. Eisenhower was very concerned at the direction Castro’s government was taking, and in March 1960 he allocated $13.1 million to the CIA to plan Castro’s overthrow. The CIA proceeded to organize the operation with the aid of various Cuban counter-revolutionary forces, training Brigade 2506 in Guatemala. Eisenhower’s successor, John F. Kennedy, approved the final invasion plan on 4 April 1961.

Over 1,400 paramilitaries, divided into five infantry battalions and one paratrooper battalion, assembled in Guatemala before setting out for Cuba by boat on 13 April 1961. Two days later, on 15 April, eight CIA-supplied B-26 bombers attacked Cuban airfields and then returned to the US. On the night of 16 April, the main invasion landed at a beach named Playa Girón in the Bay of Pigs. It initially overwhelmed a local revolutionary militia. The Cuban Army’s counter-offensive was led by José Ramón Fernández, before Castro decided to take personal control of the operation. As the US involvement became apparent to the world, and with the initiative turning against the invasion, Kennedy decided against providing further air cover. As a result, the operation only had half the forces the CIA had deemed necessary. The original plan devised during Eisenhower’s presidency had required both air and naval support. On 20 April, the invaders surrendered after only three days, with the majority being publicly interrogated and put into Cuban prisons.

The failed invasion helped to strengthen the position of Castro’s leadership, made him a national hero, and entrenched the rocky relationship between the former allies. It also strengthened the relations between Cuba and the Soviet Union. This eventually led to the events of the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962. The invasion was a major failure for US foreign policy; Kennedy ordered a number of internal investigations across Latin America. Cuban forces under Castro’s leadership clashed directly with US forces during the Invasion of Grenada over 20 years later.

12 February 1961

The Soviet Union launches Venera 1 to fly to the planet, Venus.

Venera 1, the first spacecraft to fly past Venus, was launched by the Soviet Union on February 12, 1961.

It was the second attempt by the Soviet Union to launch a craft toward Venus that month. Its sister ship, Venera-1VA No.1, failed to leave Earth orbit when launched on February 4, 1961 due to a problem with its upper stage.

The Soviets were still moving at a good speed in the Space Race and had been enjoying accomplishments with the Sputnik and Luna programs. The February 4 failure would not hold them back.

Venera 1 was launched using a Molniya carrier rocket from the Baikonur Cosmodrome. The spacecraft’s 11D33 engine was the first staged-combustion-cycle rocket engine, and also the first use of an ullage engine.

Three successful telemetry sessions were conducted that gathered solar-wind and cosmic-ray data near Earth, at the outer limit of Earth’s magnetosphere, and at a distance of 1,900,000 km. After discovering the solar wind with Luna 2, Venera 1 provided the first verification that this plasma was uniformly present in deep space.

Unfortunately, just a week after making this discovery, Venera 1’s next scheduled telemetry session failed to occur and communication was lost. It is believed that the failure was due to the overheating of a solar-direction sensor.

On May 19 and 20, 1961, Venera 1 passed within 100,000 km of Venus. With the help of a British radio telescope, some weak signals from Venera 1 may have been detected in June but, overall, communication with the spacecraft was considered ended and any data transmitted at that point is considered lost.

15 September 1961

Hurricane Carla hits land in Texas with winds of 175 miles per hour.

Hurricane Carla ranks as the most intense U.S. tropical cyclone landfall on the Hurricane history. Carla developed from an area of squally weather in the southwestern Caribbean Sea on September 3. Initially a tropical depression, it strengthened slowly while heading northwestward, and by September 5, the system was upgraded to Tropical Storm Carla. About 24 hours later, Carla was upgraded to a hurricane. The storm curved northward while approaching the Yucatán Channel. Carla entered the Gulf of Mexico while passing just northeast of the Yucatán Peninsula. By early on the following day, the storm became a major hurricane after reaching Category 3 intensity. Resuming its northwestward course, Carla continued intensification and on September 11, it was upgraded to a Category 5 hurricane. Rapidly moving northeastward, Carla’s remnants reached the Labrador Sea, Canada and dissipated on September 17, 1961.

23 January 1961

The Portuguese cruise ship, Santa Maria is hijacked by those wanting to wage war on dictator António de Oliveira Salazar.

13 August 1961

East Germany closes the border between the eastern and western sectors of Berlin top prevent attempts to escape to the West.